Automation is often discussed as though it were a single capability. In practice, it refers to several distinct system architectures that differ in what they control, how decisions are made, and where responsibility sits. Lumping these together makes it difficult to reason clearly about what is now possible, what is not, and why.

What follows is a technical overview of the main automation models in use today, from traditional workflows through to agentic systems. Our hope is that a shared vocabulary and a more accurate mental model will be helpful in deciding how and where AI can best support automation in your business.

Traditional Workflow

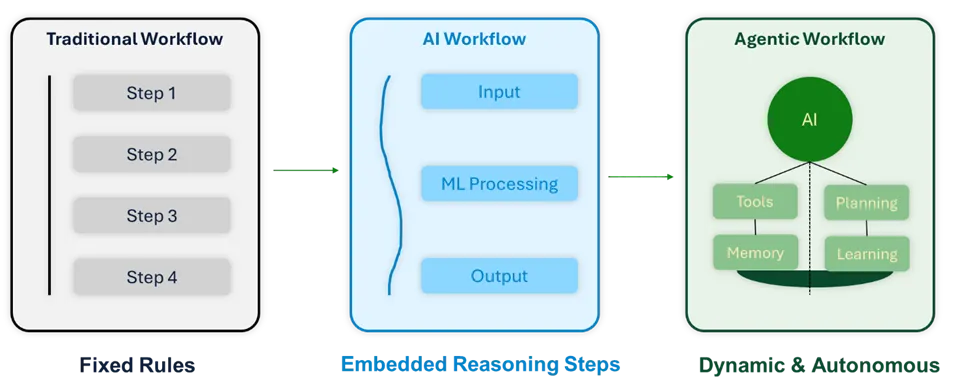

Workflow automation, in its conventional form, is based on predefined sequences of steps. A trigger initiates the workflow. Each step performs a specific action. Transitions between steps are governed by explicit rules. Inputs are expected to be structured or normalised before processing.

This model underpins BPM platforms, integration tools, and RPA systems. While the tooling varies, the abstraction is consistent. Behaviour is determined at design time. At runtime, the system executes what it has been told to execute.

This approach has several advantages. It is predictable. It is auditable. It scales well when variability is low. When it fails, it tends to fail in known and repeatable ways. For large classes of operational work, this remains entirely appropriate.

The limitations of workflow automation are structural rather than technical. Workflows assume that the sequence of actions can be known in advance and that decision logic can be fully specified. Exceptions must be anticipated and encoded. As variability increases, the workflow graph grows quickly. Exception handling becomes the dominant design concern.

In many mature environments, workflows appear automated but rely heavily on humans to resolve edge cases, reconcile inconsistencies, or make judgement calls outside the system. This is not a tooling problem. It is a consequence of the workflow abstraction itself.

AI Augmented Workflow

AI-augmented workflows extend this model without replacing it. Machine learning models are introduced into individual steps to interpret inputs or support decisions. Common examples include classification, extraction from unstructured text, summarisation, and scoring.

The workflow still determines control flow. AI improves the quality of decisions at specific points but does not decide what happens next overall. A useful way to visualise this is as a layered model: deterministic sequencing with probabilistic reasoning embedded inside selected steps.

This approach reduces manual intervention and broadens the range of inputs that workflows can handle. It does not materially change how the system is designed or governed. Planning still happens at design time. Responsibility for sequencing remains with the workflow.

Task-level automation with AI agents

A more significant change occurs when automation shifts from steps to tasks. This is where AI agents enter the picture.

An AI agent is defined less by a sequence of actions and more by an objective. It is given a goal, access to tools and systems, constraints on its behaviour, and some form of state or memory. The agent determines its own actions at runtime based on context.

This changes the unit of automation. Instead of encoding process logic externally, the system reasons about how to achieve an outcome. Planning is dynamic. The order of operations is not fixed in advance.

In practice, this allows partial automation of work that involves interpretation, coordination, or iteration. Humans remain involved, but at a higher level. They review outcomes, set boundaries, and handle cases where confidence is low or consequences are significant.

Multi-Agent Systems

As the scope of work increases, a single agent is often insufficient. Complex activities usually involve parallel concerns, internal checks, and competing criteria. Multi-agent systems address this by dividing responsibilities across specialised agents.

In such systems, different agents may gather information, evaluate options, execute actions, and monitor results. They communicate with one another and may critique or validate each other's outputs. The system's behaviour emerges from coordination rather than from a fixed control flow.

At this point, the primary challenge is no longer execution accuracy but coordination quality. Failure modes shift accordingly. Misalignment, feedback loops, and conflicting objectives become more important than missing rules or unhandled exceptions.

Agentic AI and Orchestration

Agentic AI systems extend this model further by taking responsibility for objectives rather than tasks. Given a goal and constraints, an agentic system decomposes the goal into sub-tasks, assigns work to agents or tools, monitors progress, adapts plans, and escalates when uncertainty exceeds defined thresholds.

The key distinction is that workflows are not predefined. They are generated and revised as conditions change. Autonomy here does not imply lack of control. In practice, these systems are bounded by policy, oversight mechanisms, and confidence thresholds.

Autonomy

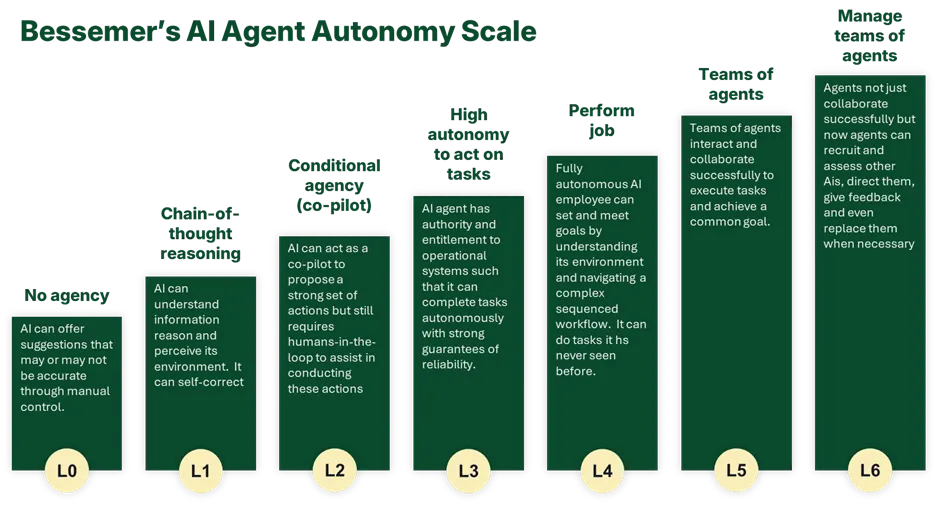

Autonomy is best understood as a spectrum rather than a binary choice. At one end, humans execute and decide. At the other, systems act independently within defined limits. Most useful applications sit somewhere in between.

This spectrum can be visualised horizontally, from human-driven execution through AI-assisted decision-making, supervised autonomy, and finally bounded autonomy. Movement along this spectrum is a design decision informed by risk, reliability, and context.

The practical reality today Is that the vast majority of AI-enabled and agentic workflow systems are being deployed at very low levels of autonomy with aspirations to decrease the need for humans-in-the-loop as capabilities mature.

Business Implications

Once these architectural distinctions are clear, the business implications become easier to assess. The most important change is that variability and judgement are no longer automatic blockers to automation. Variability can be designed around, and judgement can be designed in.

Work that involves messy inputs, conditional decisions, coordination across roles, or iterative refinement can now be partially automated in ways that were previously impractical. This does not remove humans from the loop, but it changes where their time is spent.

These systems also tend to expose underlying issues. Inconsistent policies, poor data access, and reliance on informal workarounds become visible quickly. In that sense, agentic automation often functions as a diagnostic tool as much as an efficiency measure.

For leaders, the options are not all-or-nothing. Some domains will continue to favour traditional workflows. Others benefit from augmentation. A smaller set justify agent-based or agentic approaches, typically starting in low-risk, high-variability areas.

Constraints remain real. Regulatory requirements, accountability, and organisational trust all shape where autonomy is appropriate. Governance becomes more important as systems gain discretion, not less.

The practical takeaway is that modern automation is not a single capability but a set of architectural choices. Understanding the differences between workflows, augmented systems, agents, and agentic orchestration is necessary to make sensible decisions about where automation can realistically extend, and where it should not.

These models do not represent a single path. Organisations can enter at any point based on their needs, risk appetite, and existing systems. What matters is not where you start, but whether your architecture allows you to move along the spectrum as capability and confidence grow.

The question is no longer whether automation can extend into variable, judgement-heavy work. It can. The question is where to begin, how to govern it, and how to build the organisational muscle to deploy it responsibly. That work starts now.